|

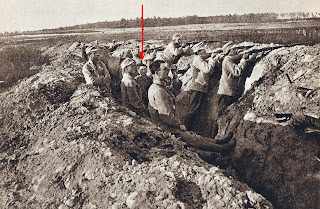

| Jaroslav Hašek, presumably somewhere in Volyn |

On 2 August 1915 the 91st regiments terrible ordeal at

Sokal came to an end. Having lost almost half of their man-power they were transferred to new position 15 km to the north, by the village of

Żdżary where they arrived early the next morning. There were disturbing reports of disloyalty in the 11th and 73rd regiment (both Czech): soldiers had thrown their guns away during the fighting, and officers were instructed to execute on the spot anyone caught. The

IR91 chronicle also reveals that the village was ridden by cholera and the troops were strictly forbidden to drink the water or eat fruit.

IR91 now joined the reserves along a section of the now relatively quiet front, which went east of the Bug. On 6 August the 3rd battalion was moved east of the river for guard duty by the

Romosz farm. On 15 August the 13th march battalion arrived and were greeted by the regimental band. It may seem insignificant, but on the list of names a certain

Leutnant Michalek is found. He is by many believed to be partly role model for the moronic lieutenant Dub, Švejk's utterly repulsive counterpart. It is also revealed that

Feldkurat Eybl that day held a glorious field mass, a parallel to

field chaplain Ibl in Švejk. About Hašek’s own undertakings, little is known from this period. A few of his poems have been preserved - “In the reserve” and “About lice”. It is also evident from official records that he was decorated for bravery on 18 August. On this day a huge celebration took place to commemorate the Emperor’s birthday, and dignitaries from the army turned up. Hašek himself was decorated by

Oberstleutnant Kieswetter.

|

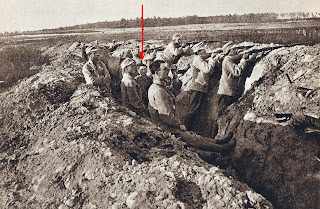

| Windmill on fire in the honour of Franz Joseph I |

The celebration also had an unsavoury twist to it that no doubt would have received the author’s attention if the novel had continued this far: the soldiers had the previous night set fire to a windmill to honour the Emperor and King. No doubt the local population was so grateful for the liberation that a destroyed livelihood would be a minor and just sacrifice in honour of the Emperor and his family who had sacrificed so much for

them. In reality the Ukrainian/Rusyn population was amongst the least loyal of all His Majesty’s subjects, and upon “liberation” in 1915 thousands of them were executed or sent to the concentration camp at

Thalerhof by Graz.

In the meantime

Conrad von Hötzendorf and his staff at

Armeeoberkommando at

Teschen (now Cieszyn/Český Těšín) were busy planning a new offensive. The aim was to push deep into Russian territory before the winter set in and cut the important north-south railway connections between

Sarny,

Rovno (Rivne) and

Tarnopol (Ternopil), and perhaps even reach

Kiev.

Historian Norman Stone observes:

Further south, the campaign ended as it had begun with an Austro-Hungarian embarrassment that, again, showed how right Falkenhayn* had been. Conrad had sought to accompany Ludendorff’s Vilna offensive with one of his own, and dreamt of a double envelopment of the twenty-five divisions of Ivanov’s front, from north and south. This took no account at all of the terrain, or the declining quality of Austrian troops. On the contrary, it was billed as ‘Black-Yellow Offensive’ it would carry the Austrians to Rovno, maybe Kiev. As Hoffmann rightly said, the Austrian high command would see sense ‘only when the knife is at their throat’. Ivanov appealed for reinforcements - sending even an eleven-page letter to the Tsar (which he did not read until March) explaining that Kiev mattered a great deal, ‘on account of the increasing numbers of pilgrims going there before the war’. But he was given only trivial reinforcement, and Conrad supposed a great victory was to be had. His troops attacked in eastern Galicia, on the Sereth, and in Volhynia. At first they made reasonable progress, taking Lutsk on 31st August. But the sick-lists rose alarmingly; transport through the marshy valleys was sometimes so slow as to be barely perceptible. Six Austro-Hungarian divisions were also removed to take part in the new Serbian offensive. In Galicia, there was a sudden reverse, with an extraordinarily high number of prisoners taken by the Russians. In Volhynia, IV Army (Archduke Joseph Ferdinand) blundered forward from Lutsk, exposing its left flank. Russians concealed themselves in the reeds and marshes, and attacked this flank between Lutsk and Rovno. By 22nd September 70,000 prisoners had been taken by the Russians, and Brusilov re-entered Lutsk. Falkenhayn had to divert to Galicia two of the Austrian divisions meant for Serbia - they had already reached Budapest - and German troops were turned south to restore the position at Lutsk. In the last days of September, Brusilov retired from Lutsk, and a line was established between it and Rovno. Conrad grumbled, after his strategic genius had once more, in his view, been betrayed: ‘We can do absolutely nothing with troops like this. Something so simple, so easy as what we planned has not been seen in the entire war, and yet we were let down’. Falkenhayn had a different verdict on these Austrian extra-tours: they were an object-lesson for Central European soldiers who thought they could defeat Russia. Austro-Hungarian losses were astonishingly high: between 1st and 25th September their force in the East fell from 500,000 to 200,000, and the proportions of loss were also remarkable - in IV Army, 30,000 ‘missing’, 10,000 wounded, 7,000 sick, 2,000 killed. It was already notable that, in the Austro-Hungarian army, twice as many officers reported sick as were wounded. In the German army, this proportion was reversed. It was good evidence of the different quality of the allied armies. Falkenhayn, not surprisingly, was glad to be relieved of the need to co-operate with Austria-Hungary on the eastern front.

*)

Erich von Falkenhayn: Chief of the German General Staff 1914-1916

At

Żdżary news about the planned offensive arrived on 24 Augus. The attack duly started on 27 August and the IR91 chronicle reports that they crossed the border 6:45 in the morning. In the beginning the 1st army, which the 9th infantry division was now assigned to, made good progress. We can from the

IR91 chronicle, “

Das Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 am Vormarsch in Galizien” easily follow Jaroslav Hašek’s route eastwards, as the movements and whereabouts of his 3rd field battalion is frequently mentioned. The battalion was still commanded by

Vinzenz Sagner with

Rudolf Lukas in charge of the 11th field company. Interestingly the commander of fourth field battalion, major

Kremžar, had on September 4

sich marod gemeldet (reported sick

). Compare the observations above from

Norman Stone on the astounding number of sick officers in the k.u.k army

...

|

The front on the Ikva and the 91st regiment.

Map by Jaroslav Šerák. |

The Russians retreated quickly and by 2 September a line on the river

Ikva was reached. The 91st regiment took up positions by

Pogorelcy on 9 September.

Dubno and its fortress had been abandoned by the Russsians on 8 September, an event reported even in official news bulletins from

Vienna. On the way the regiment passed villages like

Milatyn,

Ulgowka, Torgowica and

Mlynów and was involved in several

Gefechte on the way. The offensive however soon ground to a halt and the Russians seized the initiative. On 14 September they attacked and the positions at

Pogorelcy east of the Ikva had to be abandoned. The withdrawal took place in the night between the 17th and 18th. That night Jaroslav Hašek apparently led the whole battalion across the river Ikva, after he had used his language skill to certify where the ford was. For this deed the three years sentence he carried for desertion in

Királyhida was allegedly quashed (

Radko Pytlík,

Toulavé house, based on information from Jan Morávek, 1924). The 91st regiment and other units from the 9th division now started to dig themselves in by

Chorupan west of the river.

Early in the morning on 24 September the Russians attacked the new and still unfinished positions, and again the 91st regiment suffered disastrous losses. Although the Russians were pushed back behind the

Ikva that same day, many were killed, wounded or missing. Among the missing were two soldiers from Prague:

Jaroslav Hašek and

František Strašlipka, friends from the time in the training camp in

Királyhida. According to eyewitness accounts from

Rudolf Lukas and

Jan Vaněk Hašek was in no hurry to get away, and it is assumed that he simply let himself get captured. From that date traces of him temporarily disappeared, more on this in upcoming blogs.

![]()

The Austro-Hungarian offensive in

Volyn and Eastern Galicia ended in failure and again the losses were huge. This was the last large operation that the

Dual Monarchy undertook independently, from now on their forces were placed under German command. With the eastern front now stabilising for the winter, the 91st regiment was deemed surplus to requirements and transferred to the

Isonzo-front in Italy. In the meantime Jaroslav Hašek was “safely” interned in a miserable prisoner camp in

Orenburg oblast, southern Ural. On 15 November 1915 there was finally a report on his fate, in his favourite newspaper

Narodní politika. Here it was reported that

author Jaroslav Hašek, the well-known Czech belletrist fell in captivity at the end of September. Through this, according to "Právo lidu", all rumours about his death are disproved.

The Austro-Hungarian offensive in Volyn and Eastern Galicia ended in failure and again the losses were huge. This was the last large operation that the Dual Monarchy undertook independently, from now on their forces were placed under German command. With the eastern front now stabilising for the winter, the 91st regiment was deemed surplus to requirements and transferred to the Isonzo-front in Italy. In the meantime Jaroslav Hašek was “safely” interned in a miserable prisoner camp in Orenburg oblast, southern Ural. On 15 November 1915 there was finally a report on his fate, in his favourite newspaper Narodní politika. Here it was reported that author Jaroslav Hašek, the well-known Czech belletrist fell in captivity at the end of September. Through this, according to "Právo lidu", all rumours about his death are disproved.

The Austro-Hungarian offensive in Volyn and Eastern Galicia ended in failure and again the losses were huge. This was the last large operation that the Dual Monarchy undertook independently, from now on their forces were placed under German command. With the eastern front now stabilising for the winter, the 91st regiment was deemed surplus to requirements and transferred to the Isonzo-front in Italy. In the meantime Jaroslav Hašek was “safely” interned in a miserable prisoner camp in Orenburg oblast, southern Ural. On 15 November 1915 there was finally a report on his fate, in his favourite newspaper Narodní politika. Here it was reported that author Jaroslav Hašek, the well-known Czech belletrist fell in captivity at the end of September. Through this, according to "Právo lidu", all rumours about his death are disproved.

No comments:

Post a Comment